Annual Reflections In Depth Perspectives

scanner art by Richard Lance Williams

This Issue: Health & Well-Being

The Holiness In Health

by Laura Annawyn Shamas

In the eighteenth century, Benjamin Franklin wrote in his Poor Richard’s Almanack: “Early to bed, early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy and wise.” Centuries later, much of our civic conversations in America about “health” center on issues related to its cost and its commodification; the “wealth” or “financial” aspects of health, one might say, dominate the 21st century U.S. political dialogue. This limited approach excludes the spiritual wisdom and psychic import of health; in order to understand its meaning from an archetypal perspective, it is important to unpack the divine aspects of its origins.

In mythology, there are many examples of “the sacred” connected to “healing,” as related to medicine, health and the gods and goddesses.

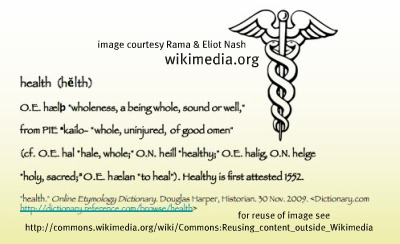

The etymology in English of the word "health" is rooted in Old English and Old Norse words: the Old English “hale” or whole; the Old Norse “heill” for healthy; the Old English “halig” and the Old Norse “helge” for holy, sacred, dedicated to the gods; and the Old English “haelen” which means to heal.1 In English, “health” is tied to the gods linguistically. The Oxford English Dictionary lists a use of the noun “health,” circa 1000 CE, as denoting a “spiritual, moral or mental soundness of being; salvation.” 2 “Salvation” signals that health is a transformative force which can protect and save; it suggests a religious, spiritual context and lexicon.

The link between ancient myth, healing, and deities is evident in many traditions. In ancient Egypt, for example, Imhotep, a key physician and vizier to Pharoah Zozer (circa 2600 BCE), was worshipped as a god by later dynasties--one of few mortals to be elevated to divine status, based on his ability to heal. Michael T. Kennedy writes in A Brief History of Disease, Science & Medicine: “By the sixth century he [Imhotep] had replaced Thoth as the god of healing.”3 Sir William Osler, the “Father of Modern Medicine,” identifies Imhotep as the Father of Medicine, “the first figure of a physician to stand out clearly from the mists of antiquity."4 The “Father of Medicine” was a god.

In Greek myth, healing is a central component in the worship of Apollo. He was given the title of “Epikourios” [“helper/healer”], and was also called “Iatros” [“doctor”]. Walter Burkert, in Greek Religion, observes: “The god of the healing hymn might well be a magician god; Apollo is just the opposite, a god of purifications and cryptic oracles…the god of purifications must also be an oracle god—however much the function of oracles later extends beyond the domain of cultic prescriptions.”5 From an archetypal angle, Apollo’s cultic prescriptions are divine, and intended to purify or “solve” a situation or problem. Consider: may comparisons be drawn between ancient oracular advice and modern medicinal prescriptions from doctors for healing herbs, lifestyle change recommendations and pharmaceuticals?

It is Asclepius, the son of Apollo, who is most remembered today as the “medicine” god of the Greek pantheon. Worldwide, many medical organizations still use a single entwined snake logo, related to Asclepius’ rod, as a branding symbol; these groups include the American Medical Association, the Australian Medical Association, the British Royal Army Medical Corps, the Canadian Medical Association, the World Health Organization, the Pakistan Army Medical Corps, the United States Air Force Medical Corps, among others.6

The twinned winged snakes on the Caduceus of Hermes were, for many years, mistakenly conflated with the Rod of Asclepius, thus highlighting a “healer” aspect of Hermes’ messenger-trickster archetype, and lending a “trickster” component to medical branding and advertising.7 Therefore, two gods, both Asclepius and Hermes, are associated with this modern symbol of medicine and healing.

There are several versions of the birth myth of Apollo’s healer-son Asclepius. Pindar’s version seems to be the most familiar; young Asclepius was miraculously birthed on a burning pyre from the womb of his mother, the dead princess Coronis, whom Apollo punished for her infidelity to the god. His mother, in this version, was royal. In another version, which is thought to explain the location of Asclepius’ extensive sanctuary at Epidaurus, Asclepius is the abandoned grandchild of the nomadic thief Phlegyas, whose chief purpose in life is to steal wealth. Phlegyas’ daughter had a secret mountain rendez-vous with Apollo. Asclepius’ mother, in this rendition, was tied to thievery. In either case, Asclepius was born at Epidaurus, and left to his own devices. A shepherd found him, but could see immediately that the child was divine; Asclepius was encircled by brilliant light. The shepherd left the god-child alone, to survive on his own with the help of a she-goat and a dog. Later, Asclepius was taught about medicine by the centaur Chiron, and his greatest medical feat was his unique ability to revive the dead.8 It was his ability to resurrect others that angered Zeus, who feared Asclepius’ powers. Zeus killed Asclepius with a thunderbolt; vengefully, Apollo retaliated by killing the Cyclopes.

Asclepius’ reach extended beyond Greece; the healing powers of Asclepius were so legendary that he, as a deity, was introduced in Rome to avert a plague in 293 BCE.9

At Epidaurus, a school of medicine flourished in Asclepius’ name; Hippocrates was among those who studied there.10 The time-honored Hippocratic Oath in its original text began with a nod to two gods and two goddesses who share a common lineage: “I swear by Apollo, the healer, Asclepius, Hygieia, and Panacea, and I take to witness all the gods, all the goddesses, to keep according to my ability and my judgment, the following Oath and agreement…”11 The Hippocratic Oath, in a modern form, is still considered relevant to the field of medical ethics. In the ancient version of the oath, the physician first acknowledges key deities before addressing the physician’s duties. There was no medical licensing in antiquity; the oath functioned as a code of honor.12Who to witness a sacred vow for healers but the gods and goddesses?

Just as gods and goddesses were associated with healing, so they were associated with the opposite: illness. Burkert writes: “The most oppressive crisis for the individual is illness. Many different gods or heroes are capable of sending illness in their wrath… Apollo’s son Asklepios proved his competence, particularly in dealing with the troubles of the individual, and thus overshadowed other healing gods and heroes.”13

The path to healing for an individual, via Asclepian rituals at Epidaurus in ancient Greece, usually involved a three day stay at the site. On the first day, the patient had to seek purity, abstain from sexual relations, and reject specific foods. Next, preliminary offerings were made; wearing a laurel wreath,14 the patient made an animal sacrifice to Apollo, and a pig sacrifice to Asclepius, along with money donated on the Asclepian altar. Before the evening “incubation,” three cakes were readied. Two were for Tyche and Mnemosyne [Success and Recollection] and one for Themis [Right Order]. If cured, the patient left behind the laurel wreath, and thanked the gods. Burkert writes: “…a successful outcome was readily accepted as the good gift of the gods that confirm the value of piety.”15 This Asclepian ritual could be seen as similar to some contemporary medical procedures: preparation for a surgery or procedure may involve the elimination of certain foods and activities beforehand; some payment is required in advance; in the end, we hope for success, a sound mind, and the completion of the correct procedures.

The goddess Hygieia [Health] was the daughter of Asclepius, and was usually depicted in his entourage.16 Hygieia was often shown, in artwork, holding a snake in her hands. As part of the ritual of Asclepius at Epidaurus, it was possible to drink directly of the goddess Hygieia--in her healing liquid form, consisting of a wheat, honey and oil concoction.17 Perhaps the modern practice of “drinking to one’s health” could be seen as related to this ancient ritual.

The goddess Panacea [Cure-All], was another daughter of Asclepius, sister to Hygieia: “she symbolizes the universal power of healing through herbs.”18 Over 300 temples and sanitoriums were built to honor Asclepius, his goddess- daughters, and his wife Epione, the goddess who could relieve pain.19 The word “Panacea” is still in use by physicians today.

For the sake of our collective well-being, our understanding of “health” in the 21st century must be “re-membered” to aspects of its mythic origins. The “Father of Medicine” is an Egyptian doctor-god Imhotep. The western concept of health is impacted significantly by Greek archetypes related to healing and medicine; the influences of Apollo, Asclepius, Hermes, Hygieia and Panacea are still evident today. Medical logos, ethics, and some practices/traditions are related to these deities. In English, the linguistic roots of the word “health” remind us of its divine essence.

It is possible to “re-vision” health in the 21st century. But in order to do so, it is imperative that we honor its sacred status in the human psyche in equal measure to modern practical concerns.

notes

1. “health.” Online Etymology Dictionary. Douglas Harper, Historian. 30 Nov. 2009. <Dictionary.com http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/health>

2. “health.” Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd Ed., 1989. 30 Nov. 2009. <http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50103662?query_type=word&queryword=HEALTH&first=1&max_to_show

=10&sort_type=alpha&result_place=2&search_id=Uthu-beNzw9-9196&hilite=50103662>

3. Kennedy, Michael T. A Brief History of Disease, Science and Medicine. Mission Viejo CA: Asklepiad Press, 2004, page 15.

4. “Imhotep.” Wikipedia. 22 Dec. 2009. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imhotep>

5. Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1985, p. 147.

6. “Rod of Asclepius.” Wikipedia.org. 22 Dec. 2009. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rod_of_Asclepius>

7. For an example of the Caduceus of Hermes, please see the image embedded with this text.

8. Grimal, Pierre. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Trans. A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996, pps. 62-63.

9. Hughes, J. Donald. Pan’s Travail: Environmental Problems of the Ancient Greeks and Romans. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins UP, 1994, p. 186.

10. Grimal, Pierre. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Trans. A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996, p. 63.

11. Hippocratic Oath.” Wikipedia.org. 22 Dec. 2009. <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocratic_Oath>

12. Pomeroy, Sarah, et al. Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, p. 462.

13. Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1985, p. 267.

14. The laurel wreath was sacred to Apollo.

15. Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1985, pps. 267-268.

16. Grimal, Pierre. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Trans. A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996, p. 219.

17. Burkert, Walter. Greek Religion. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1985, p. 268.

18. Grimal, Pierre. The Dictionary of Classical Mythology. Trans. A. R. Maxwell-Hyslop. Oxford: Blackwell, 1996, p. 141.

19. Brooke, Elizabeth. Women Healers: Portraits of Herbalists, Physicians and Midwives.Rochester, VT; Healing Arts Press, 1995, pp. 10-11.

***************************** ****************************

****************************

Author BIO

Laura Annawyn Shamas, Ph.D., is a writer and mythologist. Her study on female trinitarian archetypes, "We Three": The Mythology of Shakespeare's Weird Sisters, is published by Peter Lang (2007). Her essay "Aphrodite and Ecology: The Goddess of Love as Nature Archetype" was published in Ecopsychology, Vol. II, June 2009.

Website: laurashamas.com

Publications

"We Three": The Mythology of Shakespeare's Weird Sisters

by Laura Shamas

Publication Date: 2007 / Publisher: Peter Lang USA.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8204-7933-0 www.peterlang.com

Playwriting for Theater, Film and Television

by Laura Shamas

Publication Date: 1991 / Publisher: Betterway Books

ISBN-13: 978-15588702134

Inside This Issue: back